Transcript

This episode contains graphic descriptions that some audiences may find disturbing. Listener discretion is advised.

It’s the wee morning hours of May 30th, 1896 and you’re tossing and turning, trying to get a little sleep…but you’re not having much luck. You’re outside on the cold ground in the middle of a large field just outside of Moscow, and there are thousands of other people around you. Some of them are also trying to sleep, but many aren’t.

You’re all here for the lavish three weeks of festivities to celebrate the coronation of Russia’s new czar, Nicholas II, and his wife Alexandra. In a few hours, there will be a massive festival for the common people on the grounds where you’re currently trying to get some shut-eye — a festival that will feature an afternoon appearance by the royal couple themselves. It’s a very rare opportunity to get a glance of the monarchy that’s shrouded in mystique.

These grounds are known as Khodynka Field — a historic, ravine-riddled patch of land comprising about one square kilometer. It’s been the site of battles and celebrations, including the end of wars and the coronation festival 13 years earlier for Nicholas’s father, Alexander III. It was also the site of the All-Russian Industrial and Art Exhibition in 1882, and the remaining structures from that event were only recently torn down. So in addition to the small ravines that are a natural feature of the field, it’s now also riddled with all sorts of artificial trenches and pits from where pavilions and other structures from the exhibition were ripped out. The terrain is so uneven and pockmarked that it’s recently begun to be used for military training exercises.

But for tomorrow’s event, new infrastructure has been constructed around these blemishes. Some of the ditches, and even an old well, have simply been covered up with plywood. And new structures have been set up, including 150 kiosks for doling out free food and 20 pubs for keeping attendees boozed up with free vodka, beer and wine. This alone would have drawn a whole lot of working class folks, but what has people extra excited is the promise of royal gifts. The evening before, rumors began spreading that these gifts would be something really impressive. One rumor says the gift bag will include lottery tickets which could bestow expensive prizes or a huge fortune on a lucky few. Another rumor says that there will be commemorative cups with gold coins in them.

But for tomorrow’s event, new infrastructure has been constructed around these blemishes. Some of the ditches, and even an old well, have simply been covered up with plywood. And new structures have been set up, including 150 kiosks for doling out free food and 20 pubs for keeping attendees boozed up with free vodka, beer and wine. This alone would have drawn a whole lot of working class folks, but what has people extra excited is the promise of royal gifts. The evening before, rumors began spreading that these gifts would be something really impressive. One rumor says the gift bag will include lottery tickets which could bestow expensive prizes or a huge fortune on a lucky few. Another rumor says that there will be commemorative cups with gold coins in them.

People have flocked into Moscow from all over Russia to be part of the once in a lifetime coronation spectacle, which has sent hotel prices soaring. So many gritty commoners like yourself have come to camp out on the field to save money. But the promise of these mysterious gifts has also incentivized many to camp, to ensure that they’re in prime position to get theirs before they run out.

But many campers are making the best of this rough night and are treating it as a pre-game tailgate. Low-income Russian commoners at this time don’t often get a chance to let loose and party, so now, it seems like the riffraff from all corners of the empire have descended on Khodynka Field and left their inhibitions at home. Loud, boisterous groups are huddled around bonfires all over the field. The poet Fyodor Sologub would later describe the scene.

“They brought with them bad vodka and heavy beer, and drank all night, and bawled in hoarse, drunken voices. They ate stinking food. They sang obscene songs. They danced shamelessly. They laughed. The accordion screeched vilely. It smelled bad everywhere, and everything was disgusting, dark and scary. Here and there men and women were embracing. Under one bush two pairs of legs stuck out, and from under the bush one could hear the intermittent, disgusting squeal of satisfied passion. A drunken, noseless woman danced furiously, shamelessly waving her skirt, dirty and torn. Then she began to sing. The words of her song were as shameless as her terrible face, shameless as her terrible dance.”

Around 3am, you abandon any hope of getting a decent night’s rest and start to get up. Others are following suit, and it seems even the teetotalers are brushing off their lack of sleep to join in the reveling, laughing, and singing in giddy anticipation. But still, no one is taking their eyes off the prize.

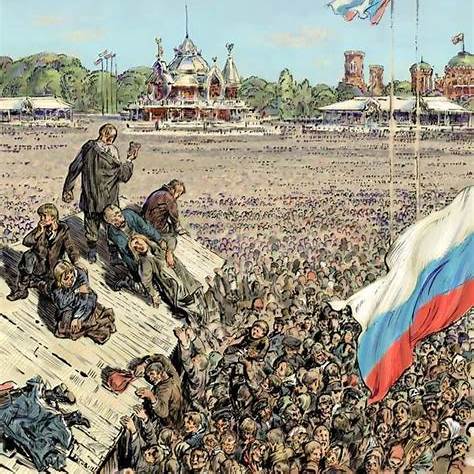

The coveted gift bags and food are to be handed out from a long row of stalls at the edge of the field protected by large barricades at 10am. So you begin to wander toward that area to check it out. But when you get there, you’re surprised to see a huge crowd already gathered seven hours early. And thousands more still are pouring in as you look on. Soon, those thousands become tens of thousands, and by 5am, hundreds of thousands. By dawn, it’s estimated there are half a million people just in the vicinity of the distribution stalls, and maybe as many as a million throughout the entire field—already dwarfing the peak of 300,000 that had showed up for Alexander’s coronation festival 13 years earlier.

Many begin to openly express concern that there won’t be enough gift bags for everyone, and they’re right to be skeptical. Organizers had indeed only prepared 400,000 bags, using turnout from Alexander’s coronation as a guide and adding what they thought would be a safe buffer of 100,000 extra. They had severely underestimated turnout.

But there won’t even be a chance for those 400,000 bags to run out before chaos ensues. The rumors are enough. One person speculates that those tasked with distributing the gifts have probably already pilfered most and given them to their friends…leaving only a small handful for the public. And like a game of telephone, off-hand remarks like that evolved and solidified into perceived fact as they’re passed around the unruly crowd.

But there won’t even be a chance for those 400,000 bags to run out before chaos ensues. The rumors are enough. One person speculates that those tasked with distributing the gifts have probably already pilfered most and given them to their friends…leaving only a small handful for the public. And like a game of telephone, off-hand remarks like that evolved and solidified into perceived fact as they’re passed around the unruly crowd.

Any semblance of orderly lines up to the barricades turn into hordes pressing in tightly against them, and then those hordes coalesce into a single condensed mass of humanity. It’s so dense that a fog has enveloped the field, made from people’s breaths in the cold morning air.

Then, a large group of workers shows up, and they’re immediately agitated at how many people there are. Not willing to accept their poor position in this dynamic, they start to violently muscle their way through the crowds toward the front. Now people are getting mad, and remember, many are already quite drunk. Mild agitation becomes loud cursing, which then escalates to shoving.

“Why are you pushing? Oh my god, they squeezed me!” a woman shouts. “Go to hell!” one of the burly workers snaps back.

“They’ll take everything, the devils, the devils!” someone else from the crowd shouts, which elevates the tension and sense of urgency even more. All the while, thousands more are pouring into the field every minute, cutting off any means of retreat, and sealing any gaps between people that remained. It’s turning this group of hundreds of thousands of individuals into one collective blob, where people are quite literally starting to lose control of their own movement and bodies.

One eyewitness later described this point in the event.

“A thick fog of steam hung over the human mass, making it difficult to distinguish individual faces at close range. The atmosphere was so saturated with vapors that people were suffocating from lack of air and the stench. It was impossible to raise their arms. And whoever raised their arms first could no longer lower them. From time to time, a distinct cracking sound was heard in the clouds of hot, noxious steam. It was a neighbor’s chest breaking.”

Things start getting desperate quickly. There are several children and babies in the crowd. Some mothers desperately try to hoist their children up and essentially crowd surf them to safety. Some are successful, but most are not.

Some begin loudly pleading for the gifts to be dispensed now in hopes that will satiate the most belligerent pushers and shovers, and begin to disperse the crowd. Those pleas then become a chant: “Distribute, distribute, distribute!”

People further back in the crowd begin to see objects flying up and arching down to those in the front, and then they hear cheers. It dawns on the crowd that the festival staff must have listened and decided to toss the gift bags out early. But you can probably guess the effect that has. Hint: it does not alleviate the situation. It backfires, and the mob takes on a life of its own.

Stalls that aren’t tossing the bags out start to get overrun and torn down. So other stalls do begin throwing theirs out to protect themselves, which just adds to the pandemonium.

The pushing and shoving becomes worse and worse. The force of those pushing from the back squeezes those in the middle ever firmer. They’re squeezed so tightly they literally can’t move their arms or legs. They’re fully at the mercy of the collective blob.

Those cheers of joy from seeing the gifts quickly become screams of agony. And the frustrated cursing from just moments ago becomes pleas of desperation, as people are crushed between masses of humanity and asphyxiated, and whole sections people collapse in unison to be summarily trampled.

Large crowd crushes are not uncommon around the world, and this one may not have been such a disaster if not for the condition of the field. That would be the final ingredient in a perfect storm. When the crowd finally dispersed, thousands would lay dead on Khodynka Field and it would have unimaginable knock-on effects. In a way, it would help precipitate the destruction of a three-century-old dynasty and fuel the global emergence of communism, on this episode of Manmade Catastrophes.

[Theme music]

As you might expect in the country that would see the world’s first Marxist regime come to power just two decades later, Russia of 1896 was a very unequal society.

At the bottom, many Russians were still subsistence farmers, and the country’s agricultural situation was among the worst in Europe. Compared to its neighbors, there was little technological advancement in farming, and little state investment in the sector—the country routinely experienced periods of famine and high inflation in food prices.

But Russia wasn’t immune to the industrial revolution underway across the continent. As the population quickly grew and food needs increased, farming was gradually starting to become more mechanized, and control of land consolidating around wealthier interests.

As this happened, more and more Russian workers were moving from the farms to factories—which were largely controlled by the state and foreign entities. Conditions for workers in these factories were predictably Dickensian—low pay, high taxes, long grueling hours, unsafe conditions, and overcrowded unsanitary housing. Worker discontent was high, and strikes and protests were routine….and illegal. Organized labor or any sort of social-political movement could be met with harsh state repression.

Then on the flipside of Russian society, you had the aristocracy—wealthy industrialists, hereditary landowners and nobility. And at the very top, you had the House of Romanov—an imperial dynasty that stretched back to 1613.

In 1894, Czar Alexander III died unexpectedly of kidney disease at age 49, leaving his son Nicholas II to assume the throne and become the 18th czar in the Romanov line at just 26 years old.

It was an open secret that Nicholas was not ready to be czar. His father had done little to prepare him for the role, he didn’t seem to have the temperament for it, and he had reportedly even told confidantes that he never even wanted the job and knew little about the business of ruling.

Many elites were skeptical of the young new leader, but for the common people, he brought some hope. His father had been an iron-fisted autocrat, and had a stern imposing physical presence to boot. Nicholas had a gentler image—the contrast in stature and demeaner between the father and son is quite apparent even from looking at old low-resolution black and white photos from the 1890s. This gave many people hope that the youthful new czar could take a gentler, more liberal and reform-minded approach to running the empire.

Nicholas’s official coronation came a year and a half after he legally ascended to the throne upon his father’s death, as is common throughout the world. There needed to be a sufficient mourning period in respect to the predecessor before this celebratory event could be held. Plus, coronations just take a long time to plan.

They tend to be expensive, lavish, and meticulously mapped out affairs in general, and Nicholas’s would even more over the top than usual. A lot had changed since his father’s coronation 13 years earlier. The world was entering a new information age, and with the proliferation of newspapers and faster communication, much of the mystique and mythmaking around the monarchy was melting away and control of the narrative weakening. That was on top of the ever-widening gulf between the haves and have-nots that industrialization was bringing. Nicholas would have to work harder than his father did to maintain that fragile support of the common man.

They tend to be expensive, lavish, and meticulously mapped out affairs in general, and Nicholas’s would even more over the top than usual. A lot had changed since his father’s coronation 13 years earlier. The world was entering a new information age, and with the proliferation of newspapers and faster communication, much of the mystique and mythmaking around the monarchy was melting away and control of the narrative weakening. That was on top of the ever-widening gulf between the haves and have-nots that industrialization was bringing. Nicholas would have to work harder than his father did to maintain that fragile support of the common man.

The coronation would be an opportunity to make a benevolent first impression with the subjects—to lavish them with splendor, excitement, food and drink, and material gifts.

It was to officially be a three-week affair full of banquets, parades, and all manner of activities, with extravagant pre-coronation festivities preceding even the official coronation events. Distinguished royalty and other dignitaries from around the world would be on hand. And another change from Alexander’s coronation would be that a lot more common people from around Russia would be able to join. Moscow’s population had grown significantly, and rail lines and transportation infrastructure generally had vastly improved–allowing people even from far flung corners of the empire to visit Moscow for the festivities.

This key development was one that event organizers apparently hadn’t accounted for. Veteran planners who had been around for all sorts of grand occasions over the decades were blindsided by the turnout—never before had so many people been able to make their way to Moscow.

Two weeks into the official coronation period, the ceremony officially anointing Nicholas as czar was held, and then the party really got started. Most of the lavish balls and banquets were reserved for a few thousand elites and dignitaries, but the event at Khodynka Field was for the working man, open to anyone who wanted to join and intended to connect the monarchy with the common people.

Most Russian workers at this time lived very meager lives and ate simple diets, consisting mostly of bread, porridge, cabbage and potatoes. Meat was a rare treat.

So the promise of raging party with fancy food was a big draw with this demographic, and the allure of free-flowing alcohol is famously one that transcends time, place and social class. But the rumored prospect of gold, or a winning lottery ticket, is what really captured the imagination of the struggling masses. Food and drink might make them happy for a day, but this mysterious gift could be life changing. That’s why so many people made it their business to get to Khodynka Field, and get there early.

Unfortunately for the masses, many of them would end up being carted off that field in wheel barrels and dumped in mass graves. And in an indirect way, it would symbolize the beginning of the end for the Romanovs—not just their reign, but their very lives.

[Ad break]

Human crushes are often incorrectly referred to as stampedes. Stampedes are a sort collective rush—usually away from a perceived threat—and composed of people running across an open route. Those who get hurt or killed are usually those who get tripped up and trampled over by those frantically running over them. Imagine a pen full of buffalo being opened and a gun fired from behind them.

But human stampedes are extremely rare, and those that become deadly disasters even more so. A crowd crush, or crowd collapse, on the other hand, is much more common. That’s defined by a high density of people. The danger isn’t from being trampled by fast moving stampeders, but rather, from people not being able to move.

Once there’s a density of around 8 to 10 people per square meter, your body starts to be firmly held in place and you start to lose control. You become swept up with the collective motion of the crowd. And that crowd can collectively collapse, leading people to be trampled or crushed under the weight. If the density and pressure is great enough, people can even become asphyxiated or crushed like an egg while still standing upright.

Once there’s a density of around 8 to 10 people per square meter, your body starts to be firmly held in place and you start to lose control. You become swept up with the collective motion of the crowd. And that crowd can collectively collapse, leading people to be trampled or crushed under the weight. If the density and pressure is great enough, people can even become asphyxiated or crushed like an egg while still standing upright.

Crushes tend to happen in very narrow bottlenecks or confined spaces, but Khodynka Field was somewhat unique in this regard. Its terrain—rough even in normal times, but especially pockmarked with ditches and holes at this point—would prove to be its fatal flaw.

Had this crush happened in a flat open field, people in the collective mob may have been squeezed, cajoled and some even trampled or smashed to death, but the human blob may have mostly remained standing and alive.

But Khodynka Field had too many opportunities for people to get tripped up, for groups to collapse, and for countless bodies to be trampled.

For instance, some of the plywood used to cover up holes and ditches had been taken by campers the night before and used as firewood—or worse, it wasn’t taken, but cracked under people’s weight, causing sudden unexpected crowd collapses. Remember that old well I mentioned earlier that had simply been boarded over. 26 corpses were later pulled out of it.

One of the deadliest spots was a 650-foot long, 7-foot deep trench with a steep drop-off where an old rail line had been ripped out. It sat only about 90 feet back from distribution tents, and that was by design. Organizers expected that it would form a natural barrier between the distribution area and the rest of the festival.

But when the crowd unexpectedly grew past that trench, it was just a matter of time before it caused a disaster. As the crowd became a crush and had ever increasing pressure from behind, people were helplessly pushed over the edge of the trench and off their feet, and more people were pushed on top of them, and then more layers still on top of them, and then those who had fallen in the trench were trampled over by even more people. In this and other trenches and ditches, dozens of mangled bodies would later be found piled up on one another.

One of the most prominent people to witness the event was the writer Leo Tolstoy. He later wrote a short story about the incident from the perspective of man named Yemelyan who encountered this trench.

“Someone painfully pushed him to his side. He became even gloomier and angrier. But before he recovered from his pain, someone stepped on his foot. His coat got stuck on something and torn. He felt anger in his heart, and he began to push with all his power on the people in front of him. But then suddenly something happened which he could not understand. Earlier, he didn’t see anything in front of him except for the people’s backs, and now suddenly everything opened ahead. He saw tents, those tents from which the gifts were supposed to be given. He rejoiced, but his joy lasted for only a minute, because he immediately realized that what had opened ahead of him opened only because all those who were in front of him and come upon a trench, some while standing, others kneeling, and fell in it. He was falling there too, over the people, on the people, and others from behind were falling on him too. And then, for the first time, fear found him. He fell. A woman in a headscarf fell upon him. He shook her off his back, wanted to retreat, but others pressed from behind and he didn’t have the strength. He leaned forward, but his feet were set on the soft people below. They grabbed him by the legs and screamed. He saw nothing, heard nothing and moved forward, treading on people.”

Some didn’t even need to fall over and get trampled to die. The crowd was packed so tightly that many died of asphyxiation while standing. One man, who was in one of the densest sections of the crush, recounted hearing screaming further away, but the intense pressure on those directly around him was enough to silence them.

“It was dawn. Blue sweaty faces, dying eyes, open mouths gasping for air, a roar in the distance, and not a sound around us. The tall, handsome old man standing next to me had not breathed for a long time. He had suffocated silently, died without a sound, and his frozen corpse swayed with us. Someone was vomiting next to me. He couldn’t even lower his head.”

Others were able to escape the crush eventually, sometimes after spending hours stuck in it. And some even got their gift bag, only to drop dead shortly after from delayed effects of the crush, like organ failure. There were accounts of people crawling into bushes, or laying out on the field to rest after escaping the mob. They used their gift bags as pillows in order to protect them, fell asleep, and never woke up.

There were even some reports of stabbings within the crush—either people trying to stab down their neighbors and alleviate the pressure on themselves, or to rob others. And some of these stabbings may have resulted in deaths. There were also definitely instances of theft during and after the crush—with some opportunists going so far as to pick the pockets or nab the gift bags from mangled corpses as they fled.

In the end though, rumors about extravagant gifts were just wishful thinking. The gift bag was nothing spectacular—it contained a roll, some sausage, gingerbread and other sweets. It did also contain an enamel commemorative mug emblazoned with an image of a crown and the year 1896, which did look pretty cool. You can see photos at our website, manmadecatastrophes.com. But there was no gold or anything of substantial value. It was a nice bag of goodies for sure, but nothing life changing…and certainly nothing to die over.

In the end though, rumors about extravagant gifts were just wishful thinking. The gift bag was nothing spectacular—it contained a roll, some sausage, gingerbread and other sweets. It did also contain an enamel commemorative mug emblazoned with an image of a crown and the year 1896, which did look pretty cool. You can see photos at our website, manmadecatastrophes.com. But there was no gold or anything of substantial value. It was a nice bag of goodies for sure, but nothing life changing…and certainly nothing to die over.

The chaos unfolded over about three hours before the mob eventually dissipated, mostly organically as people even far away began to see the stalls torn down and sensed the danger. A retreat started from the outer perimeter of the mob and worked its way inward.

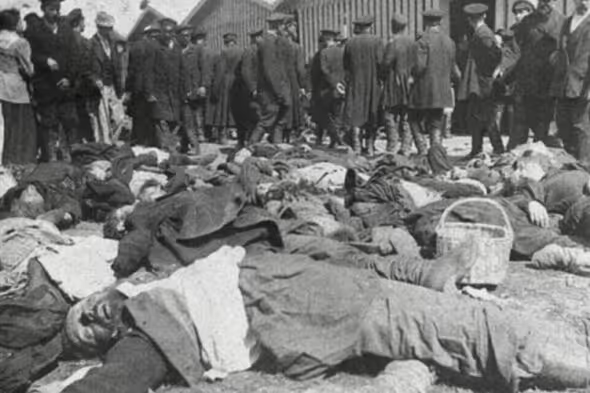

As the crowds evacuated, the extent of the devastation came into view as thousands remained sprawled across the field — dead, dying or badly wounded. In some of the larger ditches, dozens of bodies lay piled atop one another—many badly crushed and disfigured, some with mud stuffed up their nostrils and throats, indicating an especially horrific death at the bottom of the crush.

In other sections, bodies were found in similarly horrific states: scalped heads, snapped bones protruding through punctured skin, crushed rib cages, and blood everywhere.

There were some 1,800 security officers tasked with overseeing the entire field — a grossly inadequate number for managing a crowd in excess of a million people, and certainly inadequate to deal with several thousand people who were now dead or dealing with various states of injury.

But at this point, the priority is to maintain order among the living, and quickly clear out the dead and the wounded. Not necessarily tend to the wounded, but get them out as fast as possible, even if moving them risks enflaming their injuries.

After all, this is a highly important, well-publicized and symbolic celebration. It can’t be ruined—even by thousands of inconvenient deaths. A festive atmosphere needs to be restored as soon as possible, particularly since the royal couple themselves are due to show up in a few hours.

Large numbers of police, soldiers and other government workers were dispatched from around town to remove any traces of the incident. People desperately looking for missing family members were directed away from the scene. The dead and wounded were carted away as quickly as possible—to the most convenient medical facility if they were still breathing. And if not, they were taken to a morgue or makeshift storage area like a warehouse or open field where they could later be identified. Many of those who couldn’t be identified would eventually be buried in mass graves.

At around noon, the royal procession was making its way to a nearby palace and reportedly passed by a very different, macabre procession on the opposite side of the road—one of carts full of dead bodies, haphazardly covered with blankets, but some with limbs hanging out. Some people in the royal procession who had no idea what was going on reportedly thought some of these dangling arms were actually living people waving at them. But as the procession then passed the field itself, it was met by orchestras playing “God Save the Czar” and cheers from the crowd, as if nothing had happened.

At around noon, the royal procession was making its way to a nearby palace and reportedly passed by a very different, macabre procession on the opposite side of the road—one of carts full of dead bodies, haphazardly covered with blankets, but some with limbs hanging out. Some people in the royal procession who had no idea what was going on reportedly thought some of these dangling arms were actually living people waving at them. But as the procession then passed the field itself, it was met by orchestras playing “God Save the Czar” and cheers from the crowd, as if nothing had happened.

The rapid cleanup effort to erase any remnants of the tragedy was pretty successful. The disaster had begun, thousands were killed, and then it was cleaned up with scarcely a trace that anything had occurred—all within about seven hours.

Throughout that seven hours, tens of thousands of people in other parts of the field went on with the festivities, blissfully unaware of the carnage. In fact, some would spend the whole day there and go home that evening, totally oblivious that something terrible had happened so close to them. But word would quickly begin to spread.

Because of the rushed cleanup, it isn’t known exactly how many people died that day. Officially, 1,389 were killed with about another 1,300 seriously injured. But other estimates have put the probable death toll at closer to 4,000, with anywhere from 9,000 to 20,000 injured. Part of the difficulty in estimating the death toll is that many people took hours or days to die. Some fell over dead on their way home—bodies were found on the side of the road leading away from the field, in a nearby forest, and even as far as 25 miles away. Others would make it home or to a hospital, only to die there days later.

The event was an unmitigated disaster. It was very poorly planned. Organizers underestimated the number of people that would show up, they provided a grossly insufficient security force to handle crowd control, and they hosted the massive event on an uneven pockmarked plot of land where it never should have been held.

But Czar Nicholas himself wasn’t really responsible. Of course he didn’t handle the logistical minutia of the countless complicated events during the coronation period, and very few people were about to blame him for the disaster itself. But it’s what he did next that would haunt him for the rest of his reign, right up to his untimely death at the hands of a firing squad.

[Ad break]

The czar reportedly got initial word of the tragedy mid-morning, shortly after it had concluded. He didn’t yet know the full extent of the carnage, but he was told that many people had died, and by most accounts, he was sincerely disturbed by the news. Those close to him would report he was distant and sullen for the rest of the day. One of his ministers, Sergei Witte said “he looked sick and obviously depressed.”

But the question arose as to whether the festivities should go on as planned—a question that took on greater significance around mid-day as more reports came in on the true magnitude of the catastrophe.

It was ultimately decided that the show must go on. One general close to the Romanovs later recounted the situation in his memoirs.

“Many were of the opinion that the festivities should have been cancelled, but I personally do not agree with this opinion. The catastrophe had only occurred in a small area, the rest of the vast expanse of the field was full of people. There were up to a million of them, many only learned of the catastrophe in the evening. These people had come from afar, and it would hardly have been right to deprive them of the holiday. The Emperor was pale and the Empress was focused. It was obvious that they were worried; how difficult it was for them to take on and pretend as if nothing had happened.”

Now to be fair, outright canceling the festival also would have presented logistical challenges and maybe even some more dangers. Hundreds of thousands of people were cycling in and out of the field throughout the day, and it’s not like there was a PA system, or any sort of mass public text message apparatus in 1896 that could have quickly spread word. Security officials could have circulated and directed people out and prevented more from coming in, but that could have caused major congestion and chaos right around the field, or even risk angering the crowds that had come from so far, and creating another dangerous situation.

But that didn’t mean staff had to hastily sweep the disaster under the rug, eradicate any evidence of what had gone wrong, imperil the injured, and pretend like nothing had happened. But that’s the route that was taken. There was reportedly some discussion about whether the czar should perhaps go to the field immediately and console victims, or hold some sort of memorial. But that too was decided against. The festivities would go on exactly as planned.

But that didn’t mean staff had to hastily sweep the disaster under the rug, eradicate any evidence of what had gone wrong, imperil the injured, and pretend like nothing had happened. But that’s the route that was taken. There was reportedly some discussion about whether the czar should perhaps go to the field immediately and console victims, or hold some sort of memorial. But that too was decided against. The festivities would go on exactly as planned.

So the royal couple showed up at 2pm as scheduled and walked out on the balcony of the grand pavilion to wave to the cheering masses as orchestras played the national anthem and other triumphant music. Nicholas would later write in his diary that news of the disaster had left, quote, a “disgusting impression” with him and that he had thought he was going to the fair grounds for a sad occasion. But instead, quote “nothing was going on.” There was no sign of the tragedy left. So he and Alexandra simply waved to the adoring subjects, most of whom still had no idea what had happened.

But even up to this point, Nicholas’s reaction would have been forgivable. It’s what he did later that night that would turn many of those adoring subjects into harsh critics.

That night, there was a grand ball planned for the royal couple at the French Embassy hosted by the French ambassador and attended by some of the highest royalty from both countries and dignitaries from many other nations. No expense had been spared—100,000 roses had been brought in from southern France, some rooms of the embassy were converted into majestic gardens, with one room featuring an extravagant fountain lit up with novel colorful electric lights. The French had put enormous time and expense into the ball, and it was highly symbolic.

The two countries had recently formed the Franco-Russian Alliance, which brought them closer together economically and constituted an important military alliance in the face of a growing German threat.

Whether or not the royal couple should attend became an immediate controversy within the czar’s inner circle after the tragedy. Nicholas’s cousin, Duke Nikolai Mikhailovich, argued strongly against attending, making allusions to French kings prior to the French revolution. “The blood of these thousands of men, women and children will remain an indelible stain on your reign,” he reportedly told Nicholas. “Do not give your enemies a reason to say that the young tsar is dancing while his loyal subjects are being taken to the morgue”

But on the other side, more conservative family members and ministers argued that Nicholas must attend the ball. The alliance with France was too important and the ball too symbolic. They couldn’t risk leaving the impression that the new czar had snubbed the French. In fact, the French ambassador had reportedly made envoys to the royal entourage in light of the tragedy, begging that the couple still attend, at least for a short time, given that so much expense and planning had gone into the ball.

It isn’t known precisely which arguments swayed Nicholas. Later in his reign he would become known as very pliable and prone to be persuaded by the last person he talked to. But according to his younger sister Olga, he and Alexandra were sincerely reluctant to attend.

“I know for a fact that neither of them wanted to go. It was done under great pressure from his advisers. Nicky’s ministers insisted that he must go as a gesture of friendship to France.”

This would prove to be a grave blunder. For all the infamy that the czar’s attendance would gain afterwards, his actual appearance at the ball sems to have been pretty unremarkable. One countess in attendance recalled his presence.

“The czar looked all haggard and pale as a white sheet. The imperial couple walked in silence through the halls, bowing to those who had assembled. Then they went into the ambassador’s drawing room, and shortly thereafter departed. The French were in despair, but they seem to have realized that their demands after such a tragedy, one which shook the Emperor and Empress so deeply, were simply impossible.”

The royal couple reportedly did take part in a ceremonial toast and a perfunctory dance, but they did not appear enthusiastic—their distant despairing mood obvious to most. But the warnings by Nicholas’s cousin about attending the ball becoming a stain on his reign would prove very prescient. Even some of the high society types and foreign diplomats who were at the ball themselves were immediately surprised that the royal couple actually came. Chinese diplomat Li Hongzhang was apparently slightly bemused when they showed up, and quipped that the Chinese emperor never would have attended the ball after such a tragedy.

The royal couple reportedly did take part in a ceremonial toast and a perfunctory dance, but they did not appear enthusiastic—their distant despairing mood obvious to most. But the warnings by Nicholas’s cousin about attending the ball becoming a stain on his reign would prove very prescient. Even some of the high society types and foreign diplomats who were at the ball themselves were immediately surprised that the royal couple actually came. Chinese diplomat Li Hongzhang was apparently slightly bemused when they showed up, and quipped that the Chinese emperor never would have attended the ball after such a tragedy.

By all accounts, the czar’s attendance was reluctant and subdued, but the image that would trickle out to the public was one of an insensitive, out-of-touch monarch who gleefully drank champagne and danced the night away while thousands of his subjects lay dead or in agony. Later that night, Nicholas would undermine himself even further when he wrote about the day in his diary. He did begin by writing about the quote, “awful” tragedy that left a “disgusting impression” with him and noted his appearance at Khodynka Field. But after that, he signed off the day’s entry with a rather emotionless straightforward chronicle of events.

“We went to the palace, where at the gate I received several delegations and then entered the yard. Here, dinner was served under four tents for all township heads. I had to make a speech, and then another for the assembled marshals of the nobility. After going around the table, we left for the Kremlin. Dinner at Mama’s at 8. Went to the ball at the French ambassador’s. It was very nicely arranged, but the heat was unbearable. After dinner, left at 2.”

That entry would later be seized on by his critics to suggest indifference and a lack of sincere empathy. And complaining about the heat and the lavish French ball was the cherry on top.

The following day, as word was spreading around Moscow and early criticism of the royal family beginning to emerge, the imperial posture on the tragedy would do a complete 180, from basically pretending it didn’t happen, to showing sympathy and support for the victims.

Nicholas and other members of the royal family visited wounded victims in hospitals across town, and later attended funerals for the dead. He pledged 90,000 rubles of his own wealth to the victims and their families and he also sent a thousand bottles of wine to hospitals for the wounded, something that wouldn’t have been considered unusual at the time. And any children orphaned by the disaster would receive a state pension until they grew up.

Nicholas’s mother later recounted her visits with Nicholas to the hospitals.

“I was very upset seeing all these innocent victims. Nearly every one of them lost someone dear to them. But at the same time, they were so significant and noble in their simplicity that they all tried to get up and stand on their knees before the czar! They were so touching, not blaming anyone other than themselves. They even asked forgiveness for distressing the czar! You could be proud in the knowledge that you belonged to such a great and wonderful nation. Other social classes should have taken their example and not started to eat one another.”

As you might guess, comments like that didn’t exactly do much do endear the royal family to the public. For whatever later gestures they made, it was too little, too late. Nicholas’s actions on that crucial first day had set the tone…both for his handling of the tragedy itself and for his broader leadership. A shift in public sentiment was set in motion—one that would paint him as feckless, unresponsive, susceptible to bad advice, out of touch and uncaring. Many saw his gestures toward the victims as hollow and reactionary, rather than sincere.

The day after the tragedy, police tried to cajole several newspapers into not reporting on the disaster at all. But they couldn’t possibly keep a lid on thousands of deaths.

Over the following days, some of the more royal-friendly press downplayed the disaster and emphasized the royal family’s gestures of sympathy, while other more independent newspapers were highly critical of what happened—though censorship laws made them stop short of implicating any of the royals.

International newspapers though faced no such restrictions, and they were merciless—reporting what had happened in gruesome detail, probably to the point of exaggeration, and pulling no punches when it came to the czar’s post-tragedy activities. Furthermore, there were even illicit pamphlets distributed by critics of monarchy, going so far as to label the disaster the Khodynka Massacre and impugning the czar himself.

International newspapers though faced no such restrictions, and they were merciless—reporting what had happened in gruesome detail, probably to the point of exaggeration, and pulling no punches when it came to the czar’s post-tragedy activities. Furthermore, there were even illicit pamphlets distributed by critics of monarchy, going so far as to label the disaster the Khodynka Massacre and impugning the czar himself.

What happened over the following weeks didn’t help the royal family’s case. The official investigation was brief and left most people unsatisfied. Many blamed Moscow Governor General Sergei Alexandrovich, who was Nicholas’s uncle and in charge of the overall coronation activities. While he didn’t directly make the plans for the Khodynka event, he had signed off on them. So many felt the buck stopped with him, and he should bear ultimate responsibility.

But in the end, he took none. And only a few lower-level, non-royal officials were punished, and even those punishments were light. Moscow’s chief of police and his assistant, and a few other minor bureaucrats, were fired. There were no criminal charges, and the police chief would even continue to receive a generous pension for the rest of his life. No one from the royal family was officially implicated. The perception was that Nicholas was shielding his uncle, who was indeed a very important figure in the royal family, and a key adviser to the inexperienced young czar. He wasn’t about to be rebuked, putting yet another stain on Nicholas’s handling of the disaster.

And his reign wasn’t about to get any better from there. Fair assessment or not, the weakness, indecisiveness, incompetence and indifference toward commoners he had supposedly shown were seared into his public image. He would go on to be called Nicholas the Bloody by his detractors—for several reasons, but in part for the Khodynka disaster.

Whatever benefit of the doubt the public had given him was melting away. And he would go on to prove that he was not the breath of fresh air, or the reform-driven, gentler figure that people were hoping for. On the contrary, he was ironfisted yet incompetent…launching bloody crackdowns on dissent domestically, and dragging the country into catastrophic debacles internationally like the Russo-Japanese War and World War I. As historian Richard Pipes put it: “Russia had the worst of both worlds: a tsar who lacked the intelligence and character to rule yet insisted on playing the autocrat”.

What happened over the two decades following Khodynka tragedy is now well known. Nicholas completely dropped the ball, continued to alienate the beleaguered working class, gave rise to Lenin’s Bolsheviks and the Communist Revolution, and was ultimately forced to abdicate in 1917. He was subsequently imprisoned by the Bolsheviks, and the following year, taken to a basement by his guards in the middle of the night and unceremoniously executed by firing squad, along with his entire family—ending the Romanov line once and for all.

It would be a bridge too far to draw a straight line from the Khodynka tragedy to the Bolshevik Revolution and the overthrow of the Romanov Dynasty. But it did set the tone for how Nicholas, his leadership and character would be perceived by the Russian working class, and gave his opponents ample ammunition to attack him. It was a stumble that he would never really recover from. One outrage after another would pile up over the following two decades, stacked on top of the Khodynka tragedy at its base.

The symbolism was just too rich to ignore. The struggling working class scrapping and fighting for meager gifts that an all-powerful monarchy deigned to toss them, and dying by the thousands in the process. Their bodies unceremoniously dragged away so the monarchs could be celebrated and exalted on those very same grounds just hours later–then those leaders traipsing off to drink and dance at a ball lavish beyond any working man’s wildest imagination. Nicholas would have been hard up to write a better script for his enemies if he’d tried.

Of course, there’s a lot of nuance lost in that script. Hindsight is 20/20, and it’s hard to know exactly what information Nicholas had when, and all the complicated dynamics he was dealing with in various moments. Decisions that may seem outrageous in retrospect may have been perfectly logical in the moment.

The Khodynka tragedy appears to have been fundamentally caused by accidents and poor planning at lower levels rather than by any sort of malice, callousness or corruption. Perhaps the hit to his image that Nicholas took wasn’t entirely fair, but that’s often the nature of disasters—particularly those of this magnitude. They take on a life of their own and become steeped in symbolism that transcends the actual events themselves.

But certainly, any system that saw fit to immediately spring into action to try to sweep these inconvenient deaths and mortal injuries under the rug was fundamentally flawed. And Nicholas would do nothing but try to reinforce that system, clinging to absolute power he had no business holding.

[music]

That’s all for today. We used many sources for this episode, which you can find on our website at manmadecatastrophes.com, where you can also see a transcript of this episode and pictures from the Khodynka tragedy, as well as our full episode archive.

If you haven’t yet, please be sure to hit subscribe on Spotify, Apple, YouTube or any of the usual podcast platforms—and if you’d be so kind, consider leaving a review. We’ve also started creating cool little video shorts for the catastrophes we cover, so if you want to check those out, head to our YouTube, Instagram or TikTok channels. Those can all be found under the handle @manmadecatastrophes on the respective platforms, or you can check the links below in the description. Thanks again for joining, and see you soon for our next manmade catastrophe.

Sources

- “Khodynka tragedy – Nicholas II.” Nicholas II. n.d. https://tsarnicholas.org/category/khodynka-tragedy/

- “Romanov Royal Martyrs | Painful Points of Nicholas II’s Reign.” Romanovs. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://www.romanovs.eu/painful-points

- “Толпа! Урок истории – Ходынка [Crowd! History lesson – Khodynka].” Хранитель. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20160304194824/www.psj.ru/saver_national/detail.php?ID=15121

- Tolstoy, Leo. “Khodynka.” Internet Archive. Last modified January 1, 1910. https://archive.org/details/Khodynka_LevTolstoy/page/n5/mode/2up

- McGuire, Peter. “What Caused the Khodynka Tragedy?” Unlikely Explanation. Last modified January 10, 2022. https://www.unlikelyexplanation.com/post/what-caused-the-khodynka-tragedy

- “Rising Discontent in Russia | History of Western Civilization II.” Lumen Learning – Simple Book Production. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldhistory2/chapter/rising-discontent-in-russia/ “

- ХОДЫНCКАЯ КАТАСТРОФА [Khodynka Disaster].” Универсальная научно-популярная энциклопедия Кругосвет. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://www.krugosvet.ru/enc/istoriya/HODINCKAYA_KATASTROFA.html

- Kotar, Nicholas. “The Coronation of Nicholas II: Triumph and Tragedy.” Nicholas Kotar. Last modified May 11, 2023. https://nicholaskotar.com/2017/05/26/coronation-nicholas-ii-triumph-tragedy/

- “Nicholas II.” The Decline and Fall of the Romanov Dynasty. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://fallofromanovs.weebly.com/nicholas-ii.html

- DeGroot, Gerard. “The Last Tsar by Tsuyoshi Hasegawa Review — the Fatal Stupidity of Nicholas II.” The Times & The Sunday Times: Breaking News & Today’s Latest Headlines. Last modified December 14, 2024. https://www.thetimes.com/article/the-last-tsar-by-tsuyoshi-hasegawa-review-k08hj6p8t?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Каменченко, Петр. “«Ямы наполнялись людьми, толпа шла прямо по ним». Как коронация Николая II обернулась крупнейшей давкой в истории России [‘The pits were filling with people, the crowd was walking right over them.’ How the coronation of Nicholas II turned into the largest stampede in Russian history].” Lenta.RU. Last modified May 30, 2021. https://lenta.ru/articles/2021/05/30/hodinka/

- “Ходынская катастрофа 1896 года – приватный опыт судебной и строительно-технической экспертизы [Khodynka disaster of 1896 – private experience of forensic and construction-technical expertise].” Строительный и архитектурный портал «Строительный Эксперт». Last modified 2024. https://ardexpert.ru/article/27143

- Mikhailovich, Alexander. Once A Grand Duke: By Alexander Grand Duke of Russia. Vancouver: Read Books, 2020.

- “Кто начал царствовать Ходынкой…” 125 лет массовой трагедии во время коронации Николая II – Мнения ТАСС [‘Who began to reign over Khodynka…’ 125 years of mass tragedy during the coronation of Nicholas II – TASS Opinions].” TACC. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://tass.ru/opinions/11457815

- Dzhunkovsky, V.F. “Коронационные торжества 1896 года в Москве [Coronation celebrations in 1896 in Moscow].” ХРОНОС. ВСЕМИРНАЯ ИСТОРИЯ В ИНТЕРНЕТЕ. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://www.hrono.ru/libris/lib_we/1896dzhunk.html

- “Трагедия на Ходынском поле [Tragedy on Khodynka Field].” Omsk State University. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://www.univer.omsk.su/omsk/socstuds/nicholas2/4.html