Transcript

This episode contains graphic descriptions that some audiences may find disturbing. Listener discretion is advised.

It’s September 23rd, 1904 and nearly 300 children sit restlessly at their school in the village of Pleasant Ridge, Ohio on the outskirts of Cincinnati.

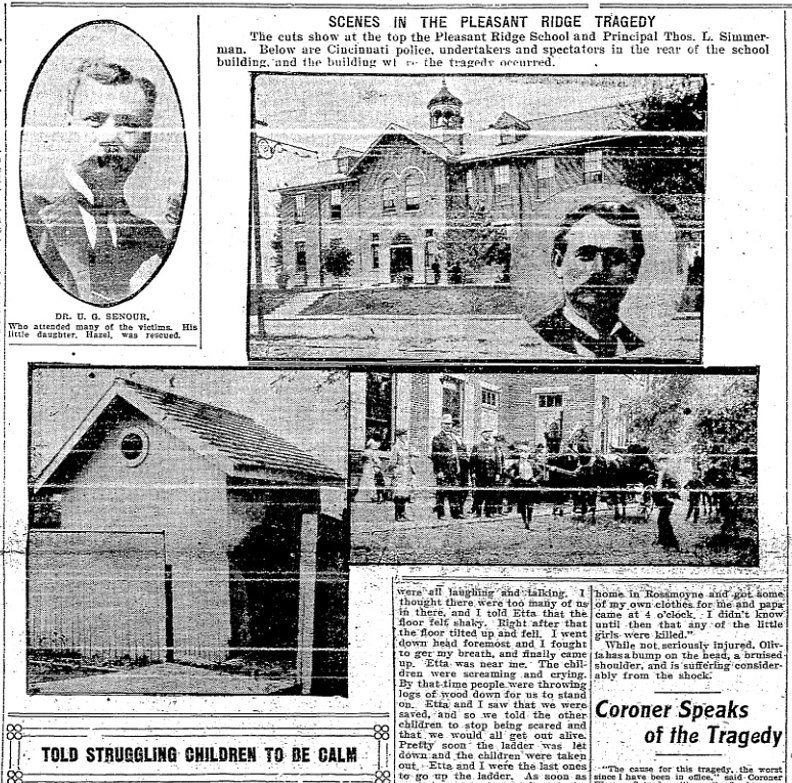

The Pleasant Ridge School teaches elementary and middle school-aged students, and this year, it’s very crowded. A school in a nearby village was recently condemned by the state, sending its 50 students to Pleasant Ridge and stretching it beyond capacity.

It’s 10am on a Friday morning, and as will happen by the end of the week, the kids are already getting antsy—something that Principal Thomas Simmerman is well-attuned to.

He looks out the window and sees that the skies are beginning to darken. The newspaper said the weather today would be fair and warm, but it looks like there could be rain after all. Simmerman worries that if the kids don’t go outside for their morning recess now, they might not get to have it at all…much to the chagrin of their teachers, who also need the break and something to siphon a bit of energy from these amped up children.

Worst case, Simmerman figures, the students might get a little light rain on them toward the end of recess. So at 10:15, he gives the rope to the school’s bell tower a good tug, delighting the hundreds of anxious students.

Once outside, most of the boys head to the baseball diamond for a quick game, while the girls break off into smaller groups all over the playground.

But it turns out, Simmerman underestimated the ominous clouds. Within a few minutes, a huge gust of wind tears through the school grounds and it begins to rain lightly. Not eager to give up on their much needed recess, the boys keep playing and many of the girls huddle up and look up at the sky…hoping it passes quickly. But unfortunately, the opposite happens. Less than a minute later, the sky opens and an intense downpour engulfs the playground.

All the boys and most of the girls bolt back for the school building. But for some of the small groups of girls on the far side of the playground, there’s a closer shelter offering them refuge: the girl’s privy.

Privy was a common term at the time for outhouse – a standalone structure without any water or plumbing where the toilets are simply built over a deep pit. It could be small with just one toilet, or it could be a larger structure with many of them. Most privies had no drainage mechanism, leaving the human waste to just keep building up over time.

If the waste accumulated faster than it could decompose, it would eventually fill the pit. Once that happened, the pit would either have to be manually emptied by ‘night soil collectors’, or the whole structure could simply be torn down and moved, with the waste-filled pit left behind and covered with dirt or other earthen materials.

So, the deeper you dug the hole from the outset, the longer the privy would last. And deep privy vaults also had added sanitation benefits, such as keeping the stench and gasses further away from privy occupants.

On the surface, the girls’ privy at the Pleasant Ridge school was a simple 10 by 10 foot square wooden structure that contained a dozen toilets. But beneath its wooden floors was a 12-foot deep vault lined like a well with a stone floor and walls that captured the waste and prevented it from seeping out into the groundwater.

At the time, 12 feet wouldn’t have been especially deep for a privy vault—particularly one that serviced hundreds of students. But still, 12 feet was deep enough that even with hundreds of uses every week, it could last a very long time before filling.

By 1904, the privy was 11 years old and had filled about one-third of the way up, leaving a four-foot deep sludgy semi-liquid cesspool of human waste.

The girls quickly filed into the privy through its one narrow door. One of the first to enter was jostled to the back of the dank, creaky building, and she would later recount that as more and more packed in, the thought of the floor collapsing flashed into her mind.

The image frightened and she immediately wanted to leave. But by this point, there was no viable path out. At the same moment, another girl vocalized similar concerns, saying “Oh, what if this was to break down with us in here?”

Most of the girls though were still only concerned with the storm. Some of the younger children, upon finding shelter, resumed playing with one another, even dancing and jumping around inside the privy.

Finally, the last few girls squeeze their way in with barely enough room left to close the door. There are now more than 30 of them, maybe as many as 35, aged 7 to 16, standing shoulder to shoulder in this stinky, dingy, dark room, the only source of light being a small circular window just below the ceiling. They’re no doubt very uncomfortable and wondering just how long they’ll be stuck here.

Unfortunately for them, their problems are about to get unfathomably worse. What happens next comes without any warning. No cracking wood, not so much as a creak or a tremor below them to signal that things are about to go horribly wrong.

The entire floor just collapses – you might even say disintegrates – in an instant. It happens so fast that survivors would later recall that there wasn’t so much as a scream from any of the girls. Even the collapse itself had no dramatic crash, no loud crack. It barely made a sound. The floor was just there one second, and gone the next.

But the speed and silence of those first few seconds belied the seemingly endless agony and terror these girls were about to endure. When that floor gave way, it plunged them 12 feet into what can only be described as worse than the depths of hell….on this episode of Manmade Catastrophes.

[Theme music]

In 1904, the United States was on the heels of the Industrial Revolution and in the early years of the so-called Progressive Era. It was a time of transition for much of the country, as the unrestrained Gilded Age and robber baron era gave way to a raft of reforms and greater regulation aimed at improving the lives of common people. But it was a slow, uneven process.

Cincinnati at this time was booming and at the forefront of American industrialization. In 1904, it had a population of more than 325,000, putting it among the top 10 largest cities in the United States, and it was still rapidly growing.

In many ways, life was quickly improving for common people amid fast economic and technological development, along with improvements in public welfare policy. But development also brought its own drawbacks.

Cities like Cincinnati faced massive challenges to public health. Modern sewage systems were still in their infancy, and rapidly growing populations pushed traditional waste management infrastructure beyond its limits.

Flush toilets did exist by this time, but they were still luxuries mostly reserved for the wealthy. In some parts of the world, they still are. So in 1904, simple outhouses, latrines and privies were still where most people went when nature called.

For most places and times throughout human history, this system worked just fine. But with cities packing more people in much more densely, one-toilet outhouses were giving way to larger muti-person privies. And the system of simply digging a big hole in the ground to dispose of waste was hitting its limits. As early as the mid-1800s, Cincinnati was already feeling growing pains from so many people doing their business so closely together.

One problem was the human waste in these growing depositories finding its way where it shouldn’t be. Shallow or poorly built latrine pits could send excrement seeping into neighbors’ cellars, or worse, into the groundwater that fed into municipal water supplies, spreading diseases like cholera, dysentery and typhoid.

But another problem was that with more and more people, there were simply more and more outhouses and privies, and many of them were being built rather poorly on the cheap. There were laws in place regulating how they could be built, but those were often flouted.

An 1859 commentary in The Cincinnati Commercial Tribune newspaper elucidated the problem.

“We have time and again warned the public of the danger accruing from dilapidated outhouses, beneath the worm-eaten floors of which yawn the disgusting receptacle of a privy vault. Hardly a week elapses that we are not called upon to chronicle some accident arising from the insecurity of these dreadful pit-traps, which should be subjected to the periodical examination of some competent person.”

In 1866, Cincinnati’s health inspector, who had the envious job of inspecting the city’s privies, noted how widespread the problem of sub-standard construction was.

“About 830 privy vaults have been inspected; and up to the present time nearly 50 percent of all those examined were either full and emitting noisome odors, or needed repairs and cleaning.”

Even 40 years later, the problem persisted, and there were routinely reports of accidents—including deaths—happening in poorly built privies. In retrospect, it’s somewhat miraculous that there wasn’t a more serious incident before 1904.

Pleasant Ridge at this time would have been on the rural outskirts of Cincinnati, and yet to be incorporated into the city. So its privies were outside the purview of city health inspectors. In fact, there was only one man tasked with inspecting all the factories, workshops and public buildings in Hamilton County, where Pleasant Ridge sat, including their privies. But he was only required to do an inspection if there was a complaint, which there never had been at the school. Most of his time was spent dealing with complaints of conditions at factories.

Pleasant Ridge didn’t quite have the glitz and glamor of the nearby city. It was mostly farming and other working-class families of meager means. The girls would have had very simple lives that were often difficult, but it was by no means the harsh Dickensian existence it may have been a few decades earlier. And despite being a rural satellite, Pleasant Ridge wasn’t exactly backwards. In fact, unlike most of the country, it did have a sewer system. The inspector would later express surprise that despite this, the Pleasant Ridge School was still using primitive privies.

The school grounds had two of these privies—one for the boys and one for the girls, which had both been built at the same time 11 years earlier in 1893 shortly after additions to the main school building.

Over that 11 years, the girls privy had been repaired on multiple occasions, including the previous year, when new toilets, flooring and siding were installed.

But crucially, the main wooden support joists that held up the original floor were left in place. Over the 11 years, they were never replaced, reinforced or even properly inspected. When the new floor was put in, the builder assumed the joists were fine and simply laid the new floor on top of the old one. So not only were any fundamental structural problems left unaddressed, they were exacerbated by the weight of an additional floor.

As the dozens of girls packed in on the day of the storm, they were likely putting more weight and pressure on those joists than they had ever held. And the extra pressure from the girls jumping and dancing may have provided the coup de gras.

Edna Gerke, a 14-year-old girl who may have been the luckiest of the lot, recounted what happened next.

“There was no crash at all. There was no noise whatever. The floor just fell. That’s all there was to it. Not a child screamed that I heard. I felt the floor going and jumped quickly, clutching to the side of the door. I was left hanging, and with all my strength I pulled myself up and out of the place.”

About five other girls were also relatively lucky. The toilet seats were secured to the wall, so they didn’t fall with the rest of the floor. The privy had been so tightly packed that several of the girls sat or stood on the toilets to make room, which would be their salvation. After the floor went, they stepped across each of the surviving toilets to make their escape.

These girls sprinted for the school building through the heavy rain that was still hammering down on them. The first two to make it back ran into Principal Simmerman, who at this point still wasn’t even aware of the torrential downpour outside. Only a few minutes had gone by since he sent the students out for recess, whereupon he went to an interior room of the school building to speak with one of the teachers.

The girls were frantic and out of breath, struggling to articulate what had happened. But Simmerman surmised that a girl had fallen into the privy vault. In the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, he would later recount this moment.

“I did not realize the awful calamity that had overcome us, but hurried in the direction of the outbuilding. On the way, I met a number of others. They were screaming wildly at the top of their voices. It was some time before one of them could compose herself sufficiently to explain what had happened.”

In the commotion, other teachers and male students were alerted by the= desperate, horrified girls that something was terribly wrong at the privy. They all rushed to see what had happened, but absolutely nothing could have prepared them for what they were about to see.

[Ad break]

For the roughly two dozen girls in the privy who weren’t lucky enough to be sitting on a toilet or within reach of the doorway, it was a straight shot down into one of the most horrific situations a human being could ever find themselves in. And sadly, for many of them, it would be a one-way trip.

The most obvious peril of being enveloped by 11 years of accumulated bodily fluids is how absolutely nauseating it would be, to put it mildly. It’s a level of disgust hardly anyone will ever experience during the course of a normal life. Even those able to keep their heads above the surface of the muck would have had to contend with the thick, noxious gases in the enclosed space—a dynamic where it would take a heroic effort just to avoid passing out.

The second peril would be the consistency of the muck. Not only would there have been the normal bodily fluids, but also materials like newspaper, corn cobs or other materials used in lieu of modern-day toilet paper, which over time could have congealed into pulpy masses.

On the surface, it likely would have been mostly liquid, particularly if recent rain had run off into the vault. But as the cesspool got deeper, it would become thicker as it consisted more of waste that had had more time to rot and congeal, forming a sludgy, wet-cement-like texture. Then at the very bottom, it would likely be very thick, almost clay-like.

These layers would form an absolute death trap—a quicksand-like glob that’s not quite liquid enough to swim in, but not quite solid enough to gain any sort of foothold.

Finally, the third peril was the darkness. There was only that one small window in the privy, which was far above where the girls were struggling for their lives, and outside was a dark stormy sky that didn’t offer any rays of sunlight.

So this is what some two dozen young girls were contending with. They were suddenly thrust down into a muck with consistency they had never encountered, in near complete darkness, breathing in overwhelming noxious gasses, and cramped together with many others desperately flailing for their lives.

Some of the taller girls who fell feet first could keep their head above certain doom. But many of the girls were shorter than the four-foot-deep muck, which would have had at least a few inches added from displacement by two dozen girls.

Anyone who fell down the vault side or head first likely didn’t stand a chance of bringing their head up to the surface as so many others flailed beside them. And even if they fell feet first, if they weren’t tall enough, they may have quickly hit the bottom from the initial fall or been quickly pushed into the deepest, thickest part of the muck, from which escape would be very difficult.

One survivor later recounted those first horrible minutes.

“I remember sinking down and smothering. When I found I could breathe again, I just felt like I was awakening from a dream. I caught hold of the stones on the side and held myself up so I could breathe. I felt the soft, struggling bodies of lots of girls around me and underneath me somewhere. They touched me. I could see some heads sometimes and then feet.”

A separate girl gave this account.

“Everything became dark. Everybody was clutching at her neighbor while there was a terrible outcry. I think every girl was crying at the top of her voice. We were all tangled up with each other and struggled to get free. I was pushed about and some attempted to climb up on my shoulders. I made a grab for a stone I could see projecting above my head, and for a moment held on, but there were so many tugging at me that the weight tore my hold loose and I went down. Even then, the struggle continued under the water. With desperation I freed myself and looking up saw daylight which I never expected to behold again.”

In this chaos, there could be no clear thinking or room for much of any thought beyond the most basic, desperate survival instincts. Almost anyone would instinctively flail, scrap and fight for their life, even if it meant grabbing or stepping on someone else, costing them theirs. One newspaper would later report that “The weaker ones were crushed down by the stronger and forced under the mass of filth to their death.”

Still, at least one story would later emerge of two girls in the vault, Elsie Schorr and Ida Breach, who instinctively grasped onto each other as they fell and then helped one another stay above the filth.

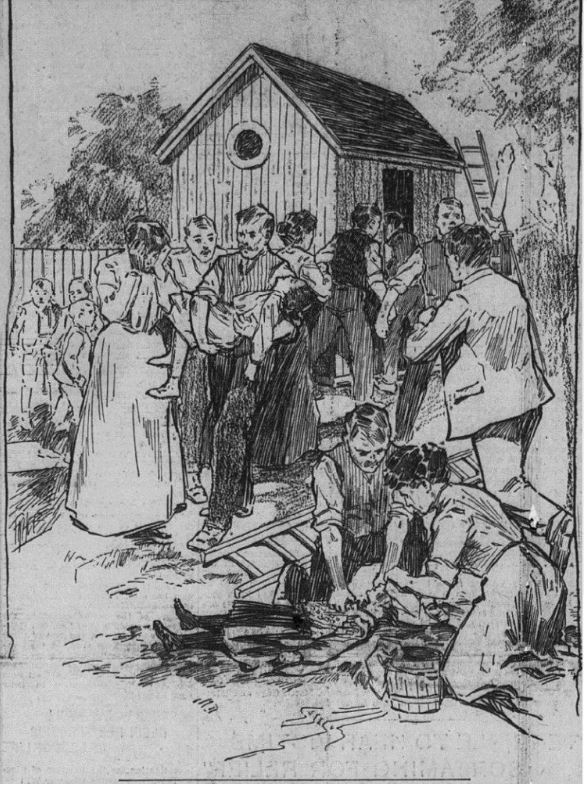

Finally, Principal Simmerman, along with another teacher and four high school boys, arrived at the privy. As Simmerman stuck his head through the narrow door, he was initially blown back by the stench. But then he forced himself through it to confront a scene straight out of a horror movie.

Aside from the toilet seats still dangling from the three walls opposite the doorway, the floor was entirely gone. And below where it once stood, there was a mass of girls flailing, some desperately trying to claw their way up the slick stone walls to no avail, and others in the middle of the vault simply trying to tread for dear life. Upon being hit by light that poured in with the open door, they began to scream “Help me! Save me!” or simply “Momma, Poppa!”

Simmerman was initially paralyzed by disbelief and horror, but after a few seconds he snapped out of it and yelled for some of the boys to find rope and ladders. As they ran off, he laid stomach down on the ground and tried to reach out to the girls. When this failed, two older boys who’d run over from a nearby church each grabbed Simmerman’s legs and helped lower him down further. This succeeded in pulling up three girls.

In the several minutes that had elapsed, the boys returned with rope from clothes lines. They lowered it in to one of the girls, Hazel Senour, who tried to use it to climb up, but then, as she was almost to the surface, it snapped, sending her plunging back into the muck, where she was pulled down by one of her struggling classmates.

Eventually, one boy ran to the bell tower and disconnected the thicker rope used to ring the school bell, and that held firm, managing to rescue another two girls.

Finally, a ladder materialized, but once lowered into the vault, it rested against the wall several feet short of the surface. So Simmerman climbed down the ladder with a rake and extended it to girls to reel them in with. Once he was able to grab onto a girl, he would pass her up the human chain with the two other young men and up to safety.

Hazel Senour, who had plunged back down the vault when that first rope snapped, would eventually regain stability and be among those rescued. She later recalled those final minutes in the vault.

“The struggle down there was terrible. As long as I could get out of the water to take a breath of air, I felt sure of being saved, but when I fell back into the hole, I thought it was all over. The girls around me were grabbing onto me. Everyone grabbed at each other, and when we did get a hold on the wall, it was only for a second. I caught hold several times, but when I was pulled at by the others, my hand slipped. There were only a few taken out, when I felt something under my feet. It must have been some little girl that had drowned. All the time I prayed. I said my prayers over and over. I could not see after a while and as I was praying to the Lord to save me, I found the rake in my hands. When I came into the light, I saw Principal Simmerman. I crawled up and was lifted out.”

As girls reached the surface one at a time, most immediately passed out, their adrenaline and survival instincts perhaps just enough to keep them conscious until the danger had passed. They were in such a putrid state, that reportedly, even a few onlookers passed out too upon seeing the rescued girls.

By this point, word had begun to spread around the village that something horrible had happened at the school, and parents were beginning to show up. Most of them reunited with their child inside the school safe and sound, having not been one involved in the disaster. But many were unable to find their child among the clean and healthy.

Those parents scoured the school rooms and nearby homes where rescued girls had been taken for treatment and cleaning up. If they failed to find their child there, they rushed back to the privy, where traumatized but breathing girls were still emerging from the narrow doorway one by one. Those parents could do nothing but look on and wait, hoping their daughter would be the next one out.

Finally, nearly an hour after the initial collapse, Simmerman pulled the 19th girl out of the privy. He looked back down into the vault, and at last, it was calm. He backed away and finally breathed a sigh of relief, thinking the terrible task was finally over. The adrenaline that had kept him going for the past hour started to dissipate and he slumped down to the ground—his energy completely drained—and his mind fluttering from the long exposure to the cloud of noxious gasses.

But one man in the crowd that’s assembled is frantically screaming. The man, John Steinkamp, has two daughters at the school, 12-year-old Emma and 8-year-old Clara. As each girl is pulled to the surface and laid on the grass, he runs over and wipes their face, hoping it’s one of his girls beneath the filth. Eventually, Clara emerges through the crowd, clean and safe, much to his relief. She had been in the privy when it collapsed but was among those few who’d escaped without actually falling down the vault. But this reunion with her father immediately becomes bittersweet when she tells him that Emma was in the privy too, and she’s still unaccounted for.

Perhaps Principal Simmerman’s mind had been too clouded by the past hour, or perhaps it was just careless wishful thinking. But it doesn’t seem to have occurred to him that there might still be girls down in the now hauntingly quiet vault.

[Ad break]

The implication of John Steinkamp’s insistence that one of his daughters is still down in the vault hits the crowd. So two men, 20-year-old William Schultz and 18-year-old John Corell, who had been two of the first on the scene and assisted with Simmerman’s rescue efforts, heroically volunteered for the terrible task of climbing down the ladder and actually wading into the cesspool to search for bodies.

Without regard for their own health and wellbeing, they climbed down the ladder, each clasping rakes that they could use to fish for bodies. Immediately upon reaching the bottom of the ladder and stepping into the muck, Schultz bumped into the first body—that of Flora Forste.

He passed her up the ladder and out to the lawn, where it was discovered that she was unconscious, but miraculously, still breathing. She was in a horrible state, and doctors didn’t think there was any way she would pull through. But a week later, she would stabilize and eventually make a full recovery. Had the two men been delayed another minute, or if Forste had been anywhere else in the vault other than right beside the ladder, it likely would have been too late for her.

Unfortunately though, she would be the last living girl to emerge from the privy. Schultz and Corell painstakingly combed the muck and would ultimately find nine more girls. They were passed up and given nitroglycerin shots in a last ditch attempt to revive them, but to no avail. None of the nine would ever wake up. The deceased ranged from age 7 to 13.

They were all taken to a classroom that became a makeshift morgue. Two of girls, 7-year-old Charmia Card and her sister, 11-year-old Fausta, were pulled from the muck wrapped so tightly in one another’s arms that they initially couldn’t be separated. They were carried to the classroom and laid down together just as they had been found.

At that time in Cincinnati, there would often be multiple editions of newspapers printed and distributed the same day, which reflected updates and breaking news. By 12:30, just a little over two hours from when the initial floor collapse had happened, the story of the privy disaster had already made it to print and was reaching people throughout the city.

Crowds of relatives, concerned citizens and curious onlookers from around the region descended on Pleasant Ridge. Roads and trains were packed and the rudimentary telephone system was overwhelmed. The sudden horrific death of nine young girls was a tragedy unlike any other the city had ever seen.

Soon after the last body was removed from the vault, the fire department was called in to pump it dry to ensure there were no bodies left. And as soon as that was done, attention turned to figuring out what exactly had gone wrong….and it didn’t take long.

After all the waste had been drained from the vault, the wood debris from the joists that had been left told the story. After examining the nine girls’ bodies, the Hamilton County Coroner Walter Weaver went to the privy, took a single glance at the wood and said, “Rotten, rotten, rotten. Everything is rotten. Those joists would not hold anything.”

Reporters on the scene reportedly picked up fragments of the wood and found it was so rotten they could easily puncture it with their umbrellas or even their fingers. To preserve the evidence, the coroner ordered that the wood debris be locked away in the school’s basement to dry.

That night, five of the six members of the village’s board of education met to take initial stock of the disaster. But their first order of business was primarily aimed at shooting down any suggestion that they were responsible. In a statement, they said:

“The Board had done all that was humanly possible to keep the building in a safe condition, having no intimation in any manner of any danger coming to the Board or any member of the Board or to the superintendent or to any one of the teachers. It had been frequently, and so far as was possible, thoroughly inspected. To our best knowledge no foresight could have prevented this tragedy.”

One member, a reverend who also oversaw buildings, said that for the previous six years, he had frequently tested the privy floors at the school himself by jumping on them with his 200-pound body, and he had last done it a month earlier.

Principal Simmerman chimed in to express how shocked they all were, claiming that nearly every day there were times when at least 40 girls filled the privy at once–a very questionable claim, given that no more than 35 girls had been in the privy that day, and that was when they were standing on toilets and barely able to close the door. He added that he often went into the privies to inspect for graffiti and never noticed anything amiss with the floor.

The meeting adjourned with the board deciding to close the school for at least a week, and to build another privy with a drainage system that wouldn’t let waste accumulate more than three feet deep.

Over the following days, more information started to come to light. Henry Swift, who had worked as a custodian at the school for nine years up until 1903, came forward. He said that shortly before he left the school, he was sweeping up the girls’ privy and noticed a beam of light beneath the floorboards down in the vault. Upon further investigation, he found that part of the stone wall that had been built on a slope had bulged inward, with some of the stones falling out to leave a two-foot-wide hole. It suggested the building’s foundation was deviating. After reporting it to the building committee, he was told to simply patch over the hole with wood planks until it could be properly repaired, but by the time he left the school several months later, it still hadn’t been fixed.

Fearing that the building wasn’t safe, before he left the school, Swift said he nailed boards over the doorway to the privy, hoping it wouldn’t be used until repairs could be made. But obviously, those boards had been removed and the privy continued to be used.

The board of education denied Swift’s account, and claimed that the foundation had been repaired immediately after his initial report. They went on to claim that in fact, it had been Swift’s own brother who laid the foundation in the first place. But most of the public seemed to side with Swift and continued to point fingers at the board.

One board member, Lewis Brewer, described the pressure they were under.

“After an accident of this kind everyone wants to make snap judgments, and no one wants to put himself in your place. I have heard many words of condemnation for our board. I’ve even heard persons on the cars say we ought to be hung.”

Whether or not Swift’s brother had laid the foundation and done it poorly, it would turn out that that was only beginning of the privy’s flaws.

Within a few days, a state inspector arrived to Pleasant Ridge with a consulting engineer to investigate the scene. Reportedly, it only took one quick look at the wood debris left from the joists and flooring to see what had gone wrong. The inspector was dumbfounded by what he saw.

“My lord, they ought not to have used yellow pine for those joists! That building had been unsafe for a long period. Gases and water in the vault would rot pine easily. Red cedar ought to have been used. Iron girders ought to have been used. This building has been unsafe almost from its erection because the girders were insufficiently fastened on the framework.”

The stone foundation was unstable, a single wood girder was used to support the weight of all the other girders, that one girder was badly attached to the foundation, and the wood that it was made from was destined to rot quickly in outhouse conditions. The building, it seemed, was doomed from the very beginning.

Once the official inquiry began, John Steinkamp—who had lost his daughter Emma—was among the witnesses. He said that after the disaster, he learned that that the first week of school that year, his daughters had mentioned to their mother that the floor of the privy was rickety. Furthermore, he had learned that a year earlier, a girl had allegedly fallen through the floor and just barely avoided plunging all the way down into the vault. Steinkamp understood that the hole was then simply boarded over without any fundamental repairs.

During his testimony, Steinkamp also expressed anger that during the rescue, 10 minutes had passed between when the last conscious girl was rescued, and when the two men went down to search for bodies and found one more survivor. That 10 minutes could have been the difference between life and death for some of those nine that perished, he argued.

Another witness at the inquiry was the carpenter who had done renovations on the privy the previous year. He had also been in the crosshairs of much of the public’s ire since the tragedy. But he strenuously defended himself, saying that he was only hired to make some cosmetic alterations, not renovate the fundamental structure of the building. “I want it thoroughly understood that I did not build that floor,” he said.

Indeed, by this point, nobdy seemed to remember who had actually built the privy originally. It had been 11 years and there were no records to shed any light. It could have been some fly-by-night contractor that was by now long gone from Pleasant Ridge.

The inquiry, which was led by Coroner Weaver, was brief, and only called on four witnesses. The verdict, which came less than a month after the disaster, was also brief. It stated that suffocation had been the cause of death of the nine girls, and there had been gross negligence on the part of the Board of Education.

“The accident occurred on account of the decayed condition of the joists supporting the floor covering of the vault,” his report read. “The floor was in such condition as to indicate that it had been laid when the joists were in a state of decay.”

However, no one was ever charged with any wrongdoing. The only apparent fallout was that for the upcoming Board of Education elections that coming November, fierce campaigns against the incumbent members immediately began to form. So in the end, none of the incumbents bothered to seek re-election.

There were immediate safety measures instituted though, including an order from the Hamilton County Board of Health that every privy vault that was part of a public building had to be immediately inspected, and routinely inspected going forward. It was also ordered that every privy vault be connected to a sewage system wherever possible.

As for the girls who had been subject to this horrific event, before the day of the disaster was even out, several funds were established around Cincinnati to support the survivors and families of the deceased.

Most of the nine girls were laid to rest two days later, and their funerals attracted crowds of mourners from around the city. Seven of the girls were buried at the Pleasant Ridge Cemetery just across the street from the school – a location many saw fitting, since children often played there after school.

Unfortunately, the funerals’ proximity to the school also sent many morbidly curious attendees to meander over to gawk at the scene of the tragedy. The privy door had been nailed shut, but that didn’t stop looky-loos from finding their way in to satiate their dark curiosity. Some people lit pieces of paper on fire and dropped them down the vault to get a better view of the conditions that had claimed nine lives.

Outside, a pile of soiled clothing that had been removed from rescued girls became its own dark attraction for onlookers, until finally someone gathered up the garments and burned them.

But while many had curiously, even mischievously, trotted over to the scene. Many were reportedly overcome by the sight of the privy vault and pile of clothes, and left in tears.

There were proposals to use some of the money that had been raised to build a marble memorial at the site of the tragedy, but some of the teachers fiercely opposed the idea, saying it would be a permanent, unwelcome reminder of what had happened. Others suggested more subtle memorials, like a simple marble shaft at the cemetery, or even just a stained glass window in the school. But those too were ultimately shot down. Many of those who’d donated to the various funds agreed with the teachers, saying they only wanted their donations used to help the victims’ families. It seems most simply didn’t want any memento—however small—that would make them think about what happened.

And that approach of ‘forget and move on’ prevailed. After the funerals, the very brief official investigation, and that initial raft of news reports and public intrigue, the whole matter quickly petered out and was basically put to rest within a matter of weeks. Even in an age of routine sensationalism and yellow journalism, media reports dried up quickly. And it seems people stopped talking about it almost entirely, at least in ways that would have made it into the public record. Though, hushed whispers and fleeting snarky comments undoubtedly persisted for decades.

At a time when modesty and decorum prevailed, ongoing public discussion of such a horrible, disgusting topic would have been considered taboo. And everyone involved, including the families, the teachers and school officials, and the city government would have had an interest in quickly moving past the ugly incident and scraping it from public remembrance.

The girls who had survived, and the families of those who hadn’t, would have had little incentive to ever mention what had happened again or do any sort of media interviews years later. Women in particular at this time were expected to maintain a certain image of purity, cleanliness, virtue and propriety—an image that would have been a bit undermined by having been enveloped by human excrement, to put it lightly.

After perhaps initially feeling incredibly blessed to be alive, and happy to tell their story of survival to reporters, the survivors likely would have learned very quickly that being known as one of the privy girls wasn’t a status likely to gain them any favor.

Even today, the few videos, articles and other posts discussing the disaster are marked by crude, lazy jokes in the comments sections — something the girls who survived no doubt would have been subject to from cruel classmates and town gossips. And like many disasters where some lived and some died, those girls likely would have been saddled with presumptions that they must have done something horrible and ruthless to scrap their way into the survivor column.

If they stayed in Cincinnati, that stigma likely would have followed them into adulthood and hampered efforts at finding romantic partners.

There’s very little information on what happened to the girls after 1904. But one can imagine social stigma was just the tip of the iceberg of what they would have dealt with for the rest of their lives.

Reports after the disaster mentioned that one of the young men who aided in the rescue and search for bodies, William Schultz, had severe pain in his lungs for weeks from the gasses in the privy, but he was expected to recover. Two of the girls were in serious condition for a week, but they too ultimately recovered. Aside from that, none of the other survivors immediately appeared to have external injuries beyond minor cuts and bruises.

Internally though, it’s likely they had problems for years, if not the rest of their lives. Being submerged in a decade’s worth of human waste would have exposed them to all sorts of bacteria, pathogens and infections.

Like Schultz, they could have developed breathing problems or lung infections from the intense gases. They likely developed digestive issues that could have lasted years. And when layered on top of the extreme nausea they would have felt during the events, that could have led to malnutrition, stomach problems and eating disorders. Skin infections could have developed, causing boils. Typhoid, hepatitis, pink eye, tetanus, E coli, cholera, dysentery, ulcers, kidney damage, intestinal worms and other parasites were all risks from the experience they had been through.

But even if they were lucky enough to escape all these physical maladies, it’s doubtful a single girl could have avoided the psychological trauma. Being in a situation where you’re both disgusted beyond anyone’s wildest imagination AND desperately flailing for your life as your friends writhe, scream and die all around you — it’s unimaginable, and in 1904, there were hardly the resources to help little girls cope with that sort of trauma.

In fact, given the social mores of the time, it’s likely their families would have pushed them to simply suppress the incident and never speak of it again. What little attention has been given to the disaster tends to focus on the nine who died. But the two dozen who survived no doubt had a large part of them die down in the vault that day as well.

It should be noted though, that according to obituary records, at least several of these girls did grow up, get married, have children, and live out the rest of their lives in Hamilton County. Those that could be found lived until they were between their mid-60s and late-80s. So whatever stigma and trauma they were contending with, it appears at least some of them did go on to live long, full lives.

Cincinnati in 1904 was a rapidly growing city dealing with the well-recognized problem of how to deal with its growing mountains of human waste. In cities dealing with breakneck growth, ubiquitous building projects and underdeveloped oversight mechanisms, accidents are bound to happen.

Unlike many manmade catastrophes, there isn’t a satisfying villain in this story. An incompetent, but anonymous and long-forgotten contractor…sure. And village education bureaucrats who fell short in overseeing safety…yeah. But it doesn’t seem there was any malice, greed or corruption involved, at least none that was apparent, which may partly explain why people were so quickly ready to forget the story and move on.

What makes it especially tragic is just how senseless and random it was. There was no comeuppance. No sense of justice. No obvious silver lining. No profound lesson, other than that you can be taken suddenly and horrifically for no rhyme or reason. Nine girls with their whole lives ahead of them were playing happily, then an hour later their lifeless bodies were being pulled from a pool of pure disgust.

It’s distressing to think that something as mundane as choosing the wrong wood for a small restroom project could result 11 years later in dozens of the most innocent people suffering the most disgusting, horrific fates imaginable. If you were a person of faith—as most strongly would have been at the time—it could well induce a spiritual crisis. How could plunging nine pure, innocent little girls to their deaths in a pit of human feces possibly be part of any righteous God’s plan? What possible meaning could there be in these nine girls’ deaths and two dozen more girls’ lifelong trauma.

These would not have been comfortable questions to grapple with, so it’s perhaps no surprise that most just preferred not to.

[Music]

This episode was based on several sources, but the most notable was a 2014 article in Belt Magazine by Richard O Jones titled “The Cincinnati Privy Disaster of 1904.” You can find links to that and other sources at our website, manmadecatastrophes.com, where you can also find a transcript of this episode and our full archive and other ways to subscribe. Thanks for listening, and we’ll see you soon for our next manmade catastrophe.

Sources